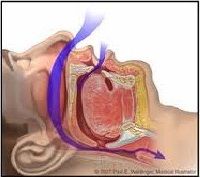

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a serious health condition characterized by a repetitive stopping or slowing of breathing that can occur hundreds of times during the night.

A variety of surgical and non-surgical options are available for the treatment of snoring and sleep apnea. In patients having difficulty with other treatments, surgical procedures for the nose and throat can be a beneficial alternative.

Surgery is an effective and safe treatment option for many patients with snoring and sleep apnea, particularly those who are unable to use or tolerate CPAP. Proper patient and procedure selection are critical to the successful surgical management of obstructive sleep apnea. The procedures are done under general anaesthesia, often with overnight hospital observation. Recovery and risks vary depending on the procedure(s) performed but are generally similar to procedures in the upper throat.

- Loud and chronic snoring

- Choking, snorting, or gasping during sleep

- Long pauses in breathing

- Daytime sleepiness, no matter how much time you spend in bed

- Waking up with a dry mouth or a sore throat

- Morning headaches

- Restless or fitful sleep

- Insomnia or nighttime awakenings

- Going to the bathroom frequently during the night

- Waking up feeling out of breath

- Forgetfulness and difficulty concentrating

- Moodiness, irritability, or depression

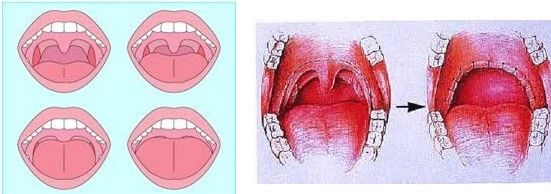

In many patients with OSA, airway narrowing and collapse occurs in the area of the soft palate (back part of the roof of the mouth), tonsils, and uvula. In general, these procedures aim to enlarge and stabilize the airway in the upper portion of the throat.

The surgery is performed in an operating room under general anaesthesia. The recovery varies depending on the patient and the specific procedures performed. Many patients return to work in approximately one week and return to normal diet and activity at two weeks. Throat discomfort, particularly with swallowing, is common in the first two weeks and usually managed with medications for pain and inflammation. Risks include bleeding, swallowing problems, and anaesthesia complications, although serious complications are uncommon.

The lower part of the throat is also a common area of airway collapse in patients with OSA. The tongue base may be larger than normal, especially in obese patients, contributing to blockage in this area. The tongue may also collapse backwards during sleep as the muscles of the throat relax, particularly when some patients sleep on their back. The epiglottis, or upper part of the voice box, may also collapse and contribute to airway obstruction.

Multiple procedures are available to reduce the size of the tongue base or advance it forward out of the airway. Other procedures aim to advance and stabilize the hyoid bone which is connected to the tongue base and epiglottis. A more recent technique involves implantation of a pacemaker for the tongue (‘hypoglossal nerve stimulator’) which stimulates forward contraction of the tongue during sleep. As with palatal surgery, the most appropriate type of procedure varies from one individual to another and is primarily determined by each patient’s anatomy and pattern of obstruction.

Structural problems, such as a deviated septum and enlarged inferior turbinates often benefit from surgical treatment. One surgical option, known as radiofrequency turbinate reduction uses radiofrequency to shrink swollen tissues in each side of the nose. The tonsils and adenoids may be the sole cause of snoring and sleep apnoea in some patients, particularly children. In children, and in select adults, with OSA and enlarged tonsils/adenoids, tonsillectomy/adenoidectomy alone can provide excellent resolution of snoring, sleep apnoea, and associated symptoms.